A recent paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences quietly did something rather dramatic. It suggested that one of the most puzzling features of recent climate change — a patch of ocean that has cooled while the planet warms — may not be a mystery after all.

This is important to understand climate models and for ocean life, fisheries, shipping and coastal communities, especially in Northern Europe and Canada — regions whose futures are intimately tied to the North Atlantic and Arctic.

Let’s take a clear look at what the study found, why it matters, and what thoughtful citizens and professionals in the North can do in response.

The climate puzzle most models couldn’t solve

We know the planet is warming. That is not in doubt. But over the satellite era (since 1979), two striking features have stood out:

- Cooling in the Southern Ocean (the ring of ocean around Antarctica), particularly in its Pacific sector.

- Cooling in the south-eastern tropical Pacific, off Peru and Chile.

Most global climate models — including those used in international assessments — simulate warming in these regions instead. That mismatch has troubled climate scientists for years.

Why does this matter?

Because patterns of ocean temperature, not just the global average, shape rainfall, storms, fisheries productivity and even the behaviour of large-scale wind systems. If we cannot simulate the pattern correctly, confidence in near-term regional projections suffers.

The new study uses a very high-resolution climate model called ICON (developed at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology). Unlike conventional models, ICON runs at kilometre-scale resolution in the ocean and atmosphere — detailed enough to simulate features normally blurred out.

And crucially, it succeeds where most models fail: it reproduces the observed cooling in both the Southern Ocean and the south-eastern tropical Pacific.

Why resolution changes everything

To understand why this matters, we need two key ideas — both simple once explained.

1. Ocean “weather”: eddies

The Southern Ocean is not smooth and steady. It is full of swirling features tens of kilometres wide called mesoscale eddies — think of them as oceanic weather systems.

Most climate models cannot simulate these eddies directly. They approximate their effects. ICON, however, resolves them explicitly.

Why does that matter?

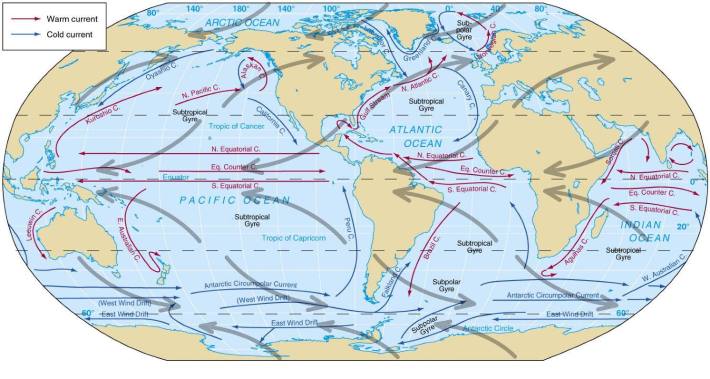

Because these eddies control how heat moves across the Antarctic Circumpolar Current — the powerful current that circles Antarctica. In ICON, heat is transported away from parts of the Southern Ocean in a way that leads to real cooling at the surface, even while greenhouse gases are rising.

This improves the model’s representation of ocean heat uptake — the process by which the ocean absorbs and redistributes excess heat from the atmosphere. The Southern Ocean alone accounts for roughly 70% of anthropogenic heat uptake. Getting it right is not optional.

2. Low clouds that amplify cooling

The second ingredient is subtropical stratocumulus cloud feedback.

Stratocumulus clouds are the extensive low cloud decks you see off the west coasts of continents. When sea surface temperatures cool slightly, these clouds can thicken and reflect more sunlight. More reflection means further cooling — a reinforcing loop.

In most climate models, this cloud feedback is too weak. In ICON, it is much closer to observations.

The result? Cooling in the Southern Ocean can influence the tropical Pacific via atmospheric circulation. Winds strengthen, evaporation increases, clouds thicken, and the cooling spreads equatorward.

In other words, the Southern Ocean and the tropics are linked more tightly than many models allow.

Why the Southern Ocean matters to the Global North

For many reasons:

- Ocean heat uptake affects global temperature trends. If models misrepresent Southern Ocean cooling, they may misjudge the pace of near-term warming elsewhere.

- Tropical Pacific patterns influence global weather. Whether the Pacific trends toward an El Niño-like or La Niña-like pattern affects rainfall, storm tracks and temperature anomalies across the North Atlantic, Scandinavia and Canada.

- Arctic amplification interacts with ocean circulation. Northern Europe and Canada are acutely sensitive to shifts in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation — the system that includes the Gulf Stream. Improved understanding of high-latitude ocean dynamics in one hemisphere strengthens modelling credibility in the other.

- Sea-ice projections depend on Southern Ocean processes. The study suggests that high-resolution models may delay Southern Ocean warming relative to conventional projections. That has implications for Antarctic ice and, indirectly, global sea level — which concerns coastal cities from Bergen to Halifax.

In short: when we improve the physics of one ocean, we improve confidence everywhere.

What should we do?

The study’s message is not merely technical. It carries policy and societal implications.

1. Support high-resolution climate modelling

Kilometre-scale models require enormous computing power and sustained funding. Northern Europe and Canada are leaders in supercomputing and climate science.

Governments, universities and funding councils can:

- Invest in next-generation Earth system modelling.

- Support open-access data sharing.

- Fund long control simulations and ensembles, not just single runs.

Better physics today means better infrastructure planning tomorrow.

2. Strengthen ocean observation systems

Models only improve when tested against observations.

Northern nations are uniquely positioned to support:

- Expanded Arctic and North Atlantic observing arrays.

- Autonomous floats (such as Argo) in subpolar waters.

- Satellite missions that track sea surface temperature and cloud properties.

If the Southern Ocean taught us anything, it is that patterns matter. Observations must resolve them.

3. Integrate ocean literacy into climate policy

Policy discussions often focus on atmospheric carbon numbers. But 90% of excess heat goes into the ocean.

Municipal planners in Scotland, Norway, Iceland, Atlantic Canada and the Baltic region should:

- Incorporate ocean heat uptake uncertainty into coastal planning.

- Recognise that short-term regional cooling does not contradict long-term warming.

- Communicate clearly that variability and forced change can coexist.

This prevents confusion when local trends temporarily diverge from global averages.

4. Accelerate decarbonisation regardless of short-term patterns

The study shows that some cooling trends may be linked to forced processes — not merely internal variability. That reinforces a crucial point: climate change is not uniform, but it is systemic. We can:

- Continue electrification of transport and heating.

- Invest in offshore wind and marine energy.

- Decarbonise shipping lanes increasingly active in Arctic waters.

- Protect and restore coastal ecosystems that absorb carbon.

Ocean processes may delay or redistribute warming — but they do not cancel it.

5. Prepare for pattern shifts

The study notes that if Southern Ocean warming is delayed, the eventual transition toward a more El Niño-like Pacific state may also be delayed.

For Northern regions, that means:

- Long-term infrastructure should be robust to shifting storm tracks.

- Fisheries management must consider multi-decadal variability.

- Insurance and risk assessment must incorporate evolving ocean-atmosphere teleconnections (a technical term for long-distance climate links).

Strategic patience and flexibility are virtues in climate governance.

A deeper lesson

Perhaps the most sophisticated takeaway is this: climate change is not merely about averages. It is about structure.

The difference between a model that blurs ocean eddies and one that resolves them can alter global temperature trends over decades. The behaviour of low cloud decks off Peru can influence rainfall patterns thousands of kilometres away.

In Northern Europe and Canada — regions accustomed to thinking in systems, from fjord hydrodynamics to Arctic sea-ice dynamics — this systemic perspective will feel natural.

The oceans are not passive heat sinks. They are active, dynamic regulators. And the better we represent their “weather”, the more reliable our climate projections become.

Kilometre-scale models are imperfect. Biases remain. Ensemble spreads are needed. But it demonstrates that processes previously invisible in standard models can reshape our understanding of recent climate trends: That is not a minor refinement. It is a conceptual advance.

The constructive response

The most intelligent response to such findings is neither complacency nor alarmism. It is seriousness.

- Serious about investing in scientific capability.

- Serious about maintaining world-leading ocean observing networks.

- Serious about communicating complexity without oversimplifying.

- Serious about reducing emissions while improving adaptation.

We have the institutional strength, scientific expertise and public literacy to lead on all four.

If the Southern Ocean has been quietly regulating planetary heat in ways we are only now properly resolving, then our responsibility is clear: resolve to match that quiet persistence with equally persistent, evidence-based climate action.

Source

Km-scale coupled simulation and model–observation SST trend discrepancy, PNAS, 2026-01-05