Hydrogen is often mooted as the fuel of the future — clean, abundant, and poised to transform not only electricity generation but heating and transport too. But how will we produce the hydrogen we need? At the centre of this puzzle lies a small, silent powerhouse: the proton exchange membrane fuel cell, or PEMFC.

A new study from SINTEF in Trondheim [63.4°N, 10.4°E], working with partners in the UK, has looked deep into the inner workings of these fuel cells, asking a deceptively simple question: If we make them thinner and cheaper, do they still work?

The answer, as is so often the case in real innovation, is not a resounding yes or no — but something far more insightful.

Doing More with Less

Fuel cells are electrochemical devices. They take in hydrogen and oxygen, and without burning anything, produce electricity, water, and heat. Their only emissions are steam. This makes them ideal for clean energy applications, especially in vehicles or remote settings.

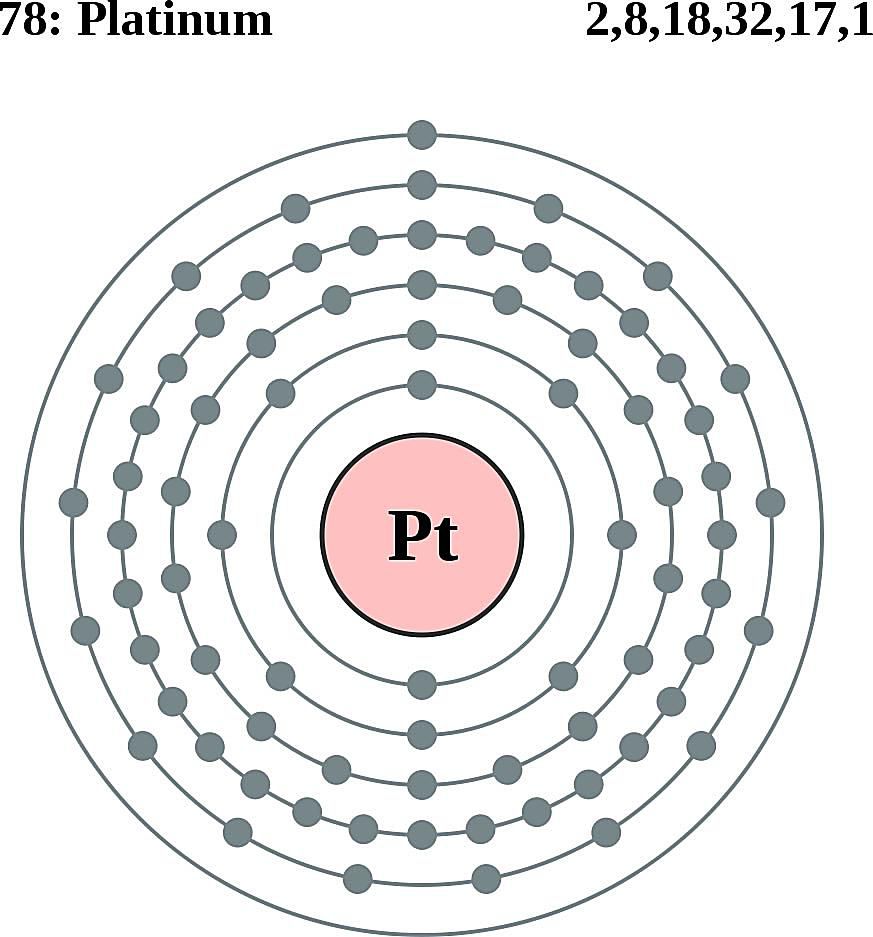

At the heart of a PEMFC is a membrane electrode assembly — a sandwich of layers where the real magic happens. Platinum catalysts split hydrogen atoms into protons and electrons; the membrane lets the protons pass while blocking everything else; the electrons go the long way around, powering a motor or a city block.

But here’s the catch: the materials are expensive, especially the platinum. In fact, the membrane and catalyst alone can make up 70% of the cost of a full-scale fuel cell. So, engineers want to use less material — thinner membranes, lighter catalyst layers — without sacrificing performance.

Does Thinner Mean Better?

In theory, a thinner membrane offers lower resistance to proton flow, making the cell more efficient. But when the researchers reduced the membrane thickness from 15 micrometres to 10, something curious happened: performance didn’t improve.

That’s not because the protons weren’t flowing. Rather, as membranes shrink, a new problem emerges. Instead of resistance through the material, the interfaces between materials — where membrane meets catalyst, or where gases pass through thin channels — become the bottleneck.

In other words, the cell doesn’t behave like a simple set of layers anymore. It starts behaving like a system of surfaces, with chemistry and physics shaped by nano-scale details. At this size, even the outer “skin” of the membrane — which becomes more hydrophobic (water-repelling) in dry conditions — can slow things down.

The Platinum Paradox

Next, the team looked at catalyst loadings — how much platinum is used. They tested fuel cells with low platinum layers (0.1 mg/cm²) versus a more conventional 0.4 mg/cm². Predictably, the thinner catalyst layers reduced performance.

But again, it wasn’t simple. The drop in performance wasn’t only because of fewer reaction sites. It came down to how gases like oxygen reach those tiny platinum particles, and how protons move through the thin ionomer films surrounding them. Thinner catalyst layers have shorter diffusion paths, but also less surface area for oxygen to cling to — a bit like trying to toast a marshmallow with just one hot coal instead of a fire.

In low-loading cells, mass transport and reaction speed become entangled. At high current densities, these limitations bite hard — and that’s where we need fuel cells to shine.

The Subtle Art of Going Thin

The real achievement of this study is not simply proving that “thinner isn’t always better.” It’s showing why, and in doing so, offering clear, quantifiable insights into how next-generation fuel cells should be designed.

Using advanced techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and CO-stripping voltammetry, the team peeled back the data to reveal:

Hydrogen crossover increases significantly in ultra-thin membranes, leading to fuel waste and membrane degradation.

Charge-transfer resistance — the measure of how easily the reaction occurs — rises sharply when platinum is reduced too far.

Mass transport resistance — how fast gases get in and out — also increases in thinner catalyst layers, but in a more nuanced way.

In short, these are the fine trade-offs that separate good lab results from viable commercial products.

Why It Matters for Sustainable Energy

For readers in Northern Europe or Canada — where hydrogen is being taken seriously as a storage solution, fuel for heavy-duty transport, or a way to balance intermittent renewables — this work matters deeply.

It means that fuel cells can get leaner, but only up to a point. More importantly, it shows where future innovation should go: not just toward minimalism, but toward smarter material interfaces, better catalyst design, and new membrane formulations that tame these microscopic inefficiencies.

It’s a bit like refining a violin. Making it thinner might lighten it, but unless the shape, tension, and grain are all tuned, you won’t get better music.

This research plays a similar role — tuning the structure of fuel cells to hit their highest possible note.

Source

The Influence of Membrane Thickness and Catalyst Loading on Performance of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 2024-10-09